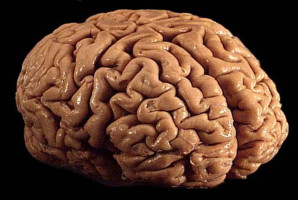

Glioblastoma is the most common – and the most malignant – primary brain tumour in adults.

It’s aggressive and incurable.

Even with treatment including surgical removal and chemotherapy, the median survival for patients is just 18 months.

Now, innovative new research led by Dr. Arezu Jahani-Asl, Canada Research Chair in Neurobiology of Disease at the University of Ottawa, provides highly compelling evidence that a drug used to slow the progression of the disease ALS shows promise in suppressing the self-renewing cancerous stem cells that challenge the present standards of care for these lethal grade 4 brain tumours.

Her team’s findings could prove highly impactful because brain tumour stem cells (BTSCs) are at the very core of therapeutic resistance and tumour recurrence in glioblastoma, a devasting and treatment-resistant type of cancer that impacts four per 100,000 people in Canada.

Indeed, discovering ways to effectively target these rare populations of highly resistant cells could have major implications for global efforts to combat brain cancer, according to Dr. Jahani-Asl, associate professor in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine and a member of the uOttawa Brain and Mind Institute.

Here’s what the uOttawa-led team found: The drug edaravone (brand name Radicava) inhibits the self-renewal and proliferation of brain tumour stem cells so repurposing the drug may prove to be a potent weapon against glioblastoma.

They reported their findings in the journal Stem Cell Reports.

“We show that edaravone specifically targets cancer stem cells and is particularly effective in combination with ionising radiation,” she says.

“The study suggests that edaravone in combination with ionising radiation can be effective in eradicating cancer stem cells, and thus is expected to decrease the chance of resistance to therapy and recurrence in glioblastoma patients.”

Ionising radiation is a type of radiation that is used in cancer therapy to kill or inhibit the growth of malignant cells.

Next steps for the researchers include writing a protocol on the best ways to optimise edaravone drug dosage in combination with ionising radiation and chemotherapy.

Repurposing existing marketed drugs already approved for human use is an increasingly popular strategy of battling different types of cancer cells.

And compounds that have already been proven safe could potentially advance swiftly to clinical trials.

Since edaravone is an approved compound that has already been shown safe in humans, Dr. Jahani-Asl says repurposing the drug and its translation for glioblastoma is “very promising.”

Edaravone was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017 to treat ALS, and Health Canada approved the drug’s oral formulation in 2022.

It’s also used to treat stroke.

Before the completed study provided compelling evidence that edaravone sensitises glioblastoma tumours to radiation therapy in animal models, the research team conducted gene expression analysis in patient-derived brain tumour stem cells in the absence and presence of the drug.

“We found significantly deregulated gene panels related to stemness and DNA repair mechanisms which was the spark to begin a new major line of investigation,” Dr. Jahani-Asl says.

Achieving new insights into BTSC regulation is at the forefront of efforts to battle glioblastoma, and Dr. Jahani-Asl is an international leader in this effort.

Her research programme at the uOttawa Faculty of Medicine is centred on developing novel therapeutic strategies for complex and devastating brain diseases.

Any new drug for glioblastoma is expected to be used in combination with the present standard treatments which includes ionising radiation and chemotherapy.

“Our goal is now to try to optimise dosage for a safe therapeutic window,” Dr. Jahani-Asl says.

“Once we establish a dose that is safe for use in combination therapy, we will be well equipped with the knowledge to move this forward to clinic.”

Source: University of Ottawa

The World Cancer Declaration recognises that to make major reductions in premature deaths, innovative education and training opportunities for healthcare workers in all disciplines of cancer control need to improve significantly.

ecancer plays a critical part in improving access to education for medical professionals.

Every day we help doctors, nurses, patients and their advocates to further their knowledge and improve the quality of care. Please make a donation to support our ongoing work.

Thank you for your support.