A University of Massachusetts Amherst cancer epidemiology researcher will explore for the first time how women’s breast tissue is affected by exposure to per-and polyfluoroalkyl (PFAS) substances that have been widely used in consumer products with non-stick, water-and stain-resistant coatings.

“Our overall goal is to understand if PFAS contribute to breast cancer development,” says Katherine Reeves, associate dean of graduate and professional studies and professor of epidemiology in the School of Public Health and Health Sciences.

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, almost everyone in the US has a measurable exposure to PFAS, one of several groups of substances called “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down naturally in the environment.

“We’re exposed to them in a variety of ways,” Reeves explains.

“Drinking water is certainly a very common one. Even though these chemicals are being phased out, we’re still using the consumer products that have these – think of the couch you bought 15 years ago that you Scotch-Guarded. You’re still being exposed. And the health effects are not entirely known.”

Previous experimental studies in animals have shown that PFAS have detrimental effects on mammary gland development and function.

“There are some human studies showing that women with higher exposure to these PFAS chemicals breastfeed for a shorter period of time,” Reeves says, possibly because their breasts stop producing milk.

In the new research, Reeves will use pre-existing data and biospecimens from the Susan G Komen for the Cure Tissue Bank, a resource that includes some 9,000 samples of breast tissue donated by healthy volunteers, along with their medical and reproductive history.

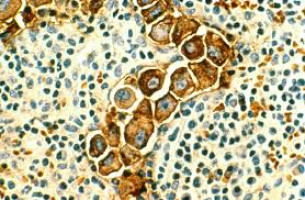

Reeves and team will examine data from 286 postmenopausal breast tissue donors who also provided a blood sample and gave access to their mammograms and measurements of their terminal duct lobular (TDL) units.

TDL produces milk after childbirth, and the “involution,” or turning on of that process, happens naturally with ageing.

“Most breast cancers come out of these terminal ductal lobular units, and a greater degree of involution is associated with a lower breast cancer risk,” Reeves explains.

The researchers will measure the concentrations of the five most common PFAS chemicals in the blood serum samples.

“We will ask the question, do we see an association between the concentration of PFAS that women have circulating and the level to which there is involution of the breast,” Reeves says.

“We’re expecting to see that PFAS concentrations will be associated with less involution, meaning that there is a higher breast cancer risk.”

The researchers will also use the volunteers’ digital mammogram files to examine breast density.

“We’ve known for years that higher mammographic density is related to an increased breast cancer risk,” Reeves says.

“And we’re going to ask the question, is PFAS concentration in the blood related to the density that we see in the breast.”

Higher PFAS concentrations associated with greater breast density would indicate a higher breast cancer risk.

It’s possible that PFAS exposure itself is associated with denser breasts, Reeves says, though many other factors, including genetics and weight, are involved.

“We’re taking advantage of these well-established biomarkers of future breast cancer risk to look at associations between PFAS and those biomarkers,” Reeves says.

The findings also will likely foreshadow the long-term effects of new, similar chemicals as the legacy PFAS chemicals are phased out.

This information may inform public health guidelines and new policies related to these classes of chemicals.

“It’s too early for us to study the health effects of these newer chemicals, but the mechanisms involved with these legacy chemicals can shed light on the health effects that we might expect to see from the newer chemicals that are being introduced today,” Reeves says.

We are an independent charity and are not backed by a large company or society. We raise every penny ourselves to improve the standards of cancer care through education. You can help us continue our work to address inequalities in cancer care by making a donation.

Any donation, however small, contributes directly towards the costs of creating and sharing free oncology education.

Together we can get better outcomes for patients by tackling global inequalities in access to the results of cancer research.

Thank you for your support.