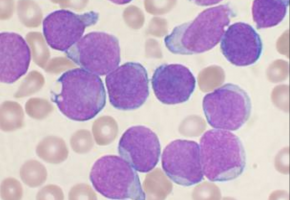

Researchers from St. Jude Children's Research Hospital and the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center have made important discoveries that could lead to better treatment for a rare blood cancer in children that has features of both leukaemia and lymphoma.

In the journal Nature, UNC Lineberger's Thomas Alexander, MD, MPH, along with co-first authors Zhaohui Gu, PhD, and Ilaria Iacobucci, PhD, of St. Jude, and corresponding authors Charles Mullighan, MBBS, MD, and Hiroto Inaba, MD, PhD, also of St. Jude, and colleagues reported findings about the genetics of mixed phenotype acute leukaemia (MPAL), a type of cancer with features of both acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL).

Their data, generated and analyzed at St. Jude, sets the stage for research into better treatment of this rare and high-risk blood cancer that accounts for approximately 3 percent of childhood acute leukaemia cases in the United States.

"Before now, no one has comprehensively studied the biology of this cancer. We were able to compile a large group of samples to characterize the genetics in these high-risk cases with features of both acute myeloid and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia," said Alexander, who is an assistant professor in the UNC School of Medicine Division of Pediatric Haematology-Oncology, and was formerly a clinical fellow at St. Jude.

Studies report a range of survival rates between 47 and 75 percent for children with mixed phenotype acute leukaemia, which also occurs in adults.

There is no consensus on the best way to treat the disease.

"ALL and AML have very different treatments. But MPAL has features of both, so the question of how best to treat patients with MPAL has been challenging the leukaemia community worldwide--and long-term survival of patients has been poor," Mullighan said.

Since the disease is rare, researchers worked with collaborators from around the world to gather samples from 115 cases to comprehensively study the biology of the disease.

They analyzed the DNA and other genetic features to better understand how the disease evolved, and to reveal treatment insights.

They found the phenotypic subtypes of this disease had different genetic features that could have treatment implications.

The T/myeloid subtype shared similarities with early T-cell precursor ALL, a finding that could inform the best treatment approach.

The B/myeloid subtype often had a change in the ZNF384 gene that is also found in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, leading researchers to believe that ALL treatment may be the best approach initially.

"That is biologically and clinically important," Mullighan said. "The findings suggest the ZNF384 rearrangement defines a distinct leukaemia subtype and the alteration should be used to guide treatment."

The researchers also discovered that within individual cases, the lymphoid and myeloid components of these tumours contain the same genetic alterations, suggesting that the mutations arose early and before the blood cells had matured into distinct types.

This finding may help explain how the cancer evolves.

"One previous theory was that the reason you have two different cancer types within the same patient is that they acquire different mutations that drive them to become AML or ALL, with genomically distinct tumours within the same patient," Alexander said. "That doesn't seem to be the case from our data. Our proposed model is that the mutations occur earlier in development in cells that retain the potential to acquire myeloid or lymphoid features."

The researchers say the next step is to determine if the laboratory insights can translate into improving clinical outcome for patients with mixed phenotype acute leukaemia.

"On this basis of this data and other recent publications, the Children's Oncology Group is in the final stage of planning a protocol that will enroll patients with mixed phenotype leukaemia on a prospective trial for the first time ever," Alexander said.