Research led by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital has identified three genetic alterations to help identify high-risk paediatric patients with acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia (AMKL) who may benefit from allogeneic stem cell transplants.

The study, which appears today in the scientific journal Nature Genetics, is the largest yet using next-generation sequencing technology to define the genetic missteps that drive AMKL in children without Down syndrome.

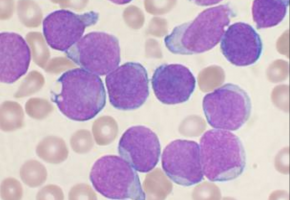

AMKL is a cancer of megakaryocytes, which are blood cells that produce the platelets that help blood clot.

The genetic basis of AMKL in children with Down syndrome was previously identified, but the cause was unknown in 30 to 40 percent of other paediatric cases.

"Because long-term survival for paediatric AMKL patients without Down syndrome is poor, just 14 to 34 percent, the standard recommendation by many paediatric oncologists has been to treat all patients with allogeneic stem cell transplantation during their first remission," said senior and co-corresponding author Tanja Gruber, M.D., Ph.D., an associate member of the St. Jude Department of Oncology.

Allogeneic transplants use blood-producing stem cells from a genetically matched donor.

"In this study, we identified several genetic alterations that are important predictors of treatment success," she said. "All newly identified paediatric AMKL patients without Down syndrome should be screened for these prognostic indicators at diagnosis. The results will help identify which patients need allogeneic stem cell transplants during their first remission and which do not."

The alterations include the fusion genes CBFA2T3-GLIS2, KMT2A and NUP98-KDM5A, which are all associated with reduced survival compared to other paediatric AMKL subtypes.

Fusion genes are created when genes break and reassemble.

Such genes can lead to abnormal proteins that drive the unchecked cell division and other hallmarks of cancer.

Researchers also recommended testing AMKL patients for mutations in the GATA1 gene.

GATA1 mutations are a hallmark of AMKL in children with Down syndrome, who almost always survive the leukaemia.

In this study, AMKL patients with GATA1 mutations and no fusion gene had the same excellent outcome.

"The results raise the possibility that paediatric AMKL patients without Down syndrome who have mutations in GATA1 may benefit from the same reduced chemotherapy used to treat the leukaemia in patients with Down syndrome," Gruber said.

The revised AMKL diagnostic screening and treatment recommendations are being implemented at St. Jude.

AMKL is rare in adults, but accounts for about 10 percent of paediatric acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).

This study involved next-generation sequencing of the whole exome or RNA of 89 paediatric AMKL patients without Down syndrome.

The patients were treated at collaborating institutions in the U.S., Europe and Asia.

Along with the sequencing data, researchers analysed patients' gene expression and long-term survival.

The results showed that non-Down syndrome paediatric AMKL can be divided into seven subgroups based on the underlying genetic alteration, pattern of gene expression and treatment outcome.

The AMKL subgroups include the newly identified HOX subgroup.

About 15 percent of the 89 patients in this study were in the HOX subgroup, which is characterised by several different HOX fusion genes.

Normally HOX genes help regulate development, but HOX alterations have been reported in other types of leukaemia.

Investigators also identified cooperating mutations that help to fuel AMKL in different subgroups.

The cooperating mutations include changes in the RB1 gene and recurring mutations in the RAS and JAK pathways in cells.

The alterations have been reported in other cancers.

Source: Nature Genetics